Nadia Rhook, La Trobe University

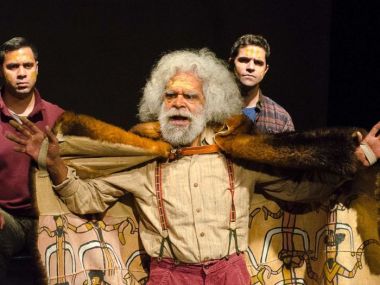

Actor and Coranderrk descendant Uncle Jack Charles playing William Barak in Coranderrk: we will show the country (Photo by Patrick Boland)

In recent years Melburnians have been educated about an episode of Australian history previously little known in non-Indigenous circles. A play, Coranderrk: we will show the country, has been performed in theatres around Melbourne, and this month will show on the former site of Coranderrk Aboriginal mission, 70 kilometers northeast of central Melbourne. It’s a poignant re-enactment of an 1881 Victorian Parliamentary hearing, where Aboriginal residents protested the proposed change of mission manager. Predicting that the new manager would thwart the success of their hop farm, and hence hinder their land rights movement, the Wurundjeri leader, William Barak, spoke forcefully against the proposed change of management.

When I saw the play in 2012, I realised that, contrary to my assumptions, the politics of Aboriginal land rights had long been an urban phenomenon.[1] In this, historians have documented, Melbourne isn’t unique. The halls of power of cities across the globe have heard Indigenous people’s protests against their entwined economic marginalisation and dispossession. The Coranderrk story, along with my research into migration, has propelled my curiosity to interrogate the city space where I live, and ask a question posed by numerous historians and thinkers before me; What’s particularly settler colonial about Melbourne’s form?

Parliament House, to which, in the late nineteenth century, Barak and his entourage twice marched to present petitions to Parliament, is situated at the elevated end of inner Melbourne. When it was built in 1851, Parliament commanded a view of the entire city; a highly planned order of streets; a grid if there ever was one. Laid in the short space of a few months in 1837, the city comprised of 24 rectangular blocks.

From its 1837 making, many colonists and visitors celebrated Melbourne’s inner street grid for its neatness; a layout intuitive for pedestrians’ navigation. Yet the grid afforded more than ease of viewing and mobility. The neat rectangular forms of the street blocks, so historian Paul Carter has written, had an important capitalist function.[2] They could be, and were, divided up into smaller rectangular allotments, just the size to attract settlers to migrate to the Antipodes from the other side of the world, most from Britain, and lesser numbers from from Germany, Italy, Switzerland, and France and other countries.

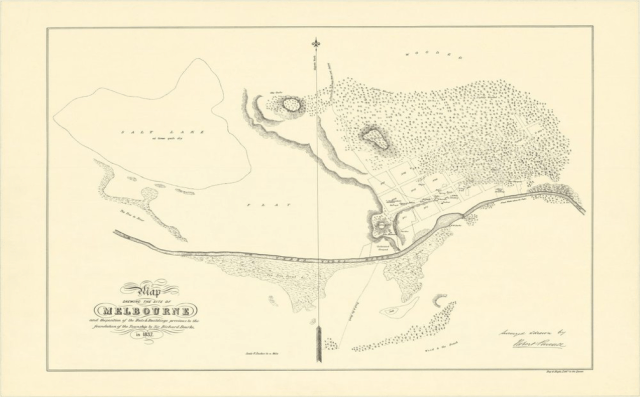

Robert Russell, ‘Map Shewing the Site of Melbourne’, 1837

These plots proved to be highly affordable and desirable to European settlers, and the population grew rapidly, from 177 people in May 1836 to some 3,000 in September 1839. As the street grid of inner Melbourne was, from its conception, embroiled in the project of dispossession, so too was its namesake, the England-born surveyor Robert Hoddle. In the same year as Hoddle was commissioned to design the grid, he was appointed auctioneer of the first sale of crown land. On 1 June 1837, he sold 100 half-acre allotments, and himself bought 2 allotments for a total of £54; a sum more than covered by his commission of £57. These land sales were performed without the consent of the Kulin nations, coming around two years after a young Barak witnessed a land hungry convict-cum settler, John Batman, make a treaty with Wurundjeri leaders, notably with nguruangaeta Billebellary.[3] To cut a contentious story short, the treaty, however, didn’t have the Crown’s assent and was quickly dissolved by the presiding Governor.[4] Consequently, the 1837 land sales literally firmed the grid foundation upon which settlers would assert their sovereignty to build and maintain gross racial inequalities.

Elisha Noyce, ‘Collins Street – Town of Melbourne, Port Philip’, 1838

The construction and maintenance of Melbourne was not only a matter of buildings and streets, but also one of water. The fresh water that flowed through the Yarra River was a matter of life for both sides of the settler/Indigenous divide. Before Europeans imposed the grid on the gently undulating hills that lie by the Yarra River, the Wurundjeri and Boonworrung peoples of the Kulin nations had inhabited the land around the Hoddle grid for at least 60,000 years. Hence the establishment of Melbourne in the heart of Kulin meeting grounds was no accident. It was built near a rocky bar across the Yarra that separated the brackish tidal water downstream from the fresh water upstream, furnishing the infant settlement with water for drinking and washing, people, plants and horses.

The five Kulin Nations

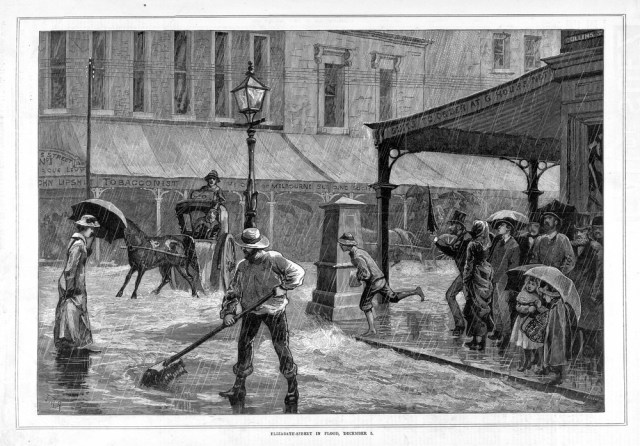

While the colonial project required fresh water to support the lives and livelihoods of settlers, the construction of Melbourne in a rain basin raised issues for settler and governmental imperatives of property and profit. A natural low point in the middle of the Hoddle grid built over a tributary of the Yarra, Elizabeth Street is infamous for defying settlers’ attempts to manipulate the country into saleable property. In the first decades of European settlement, it regularly flooded, and in ‘rainy weather [was] impassible without the means of a punt.’ As the 1882 image below shows, too much rain transformed Elizabeth Street into a soggy spectacle, exposing the uncomfortable fact that people’s accessibility to the private and Crown-owned properties of the Hoddle grid was (and is) conditioned by the confinement of water to drains and pipes, and its minimal flow along streets and into buildings.

F. A. Sleap, ‘Elizabeth Street in flood’, 1882

The story of Elizabeth Street’s susceptibility to flooding circulates amongst non-Indigenous Melburnians as a quirky story of the enduring power of nature to interrupt the intended form of the city. To be sure, settlers were determined that the buildings on this street would be accessible – and by shoe, not by punt. But in thinking about the making of Melbourne as a settler colonial city, we can recognise that the struggle to keep Elizabeth Street dry isn’t merely a story of “nature v man plan”. It’s also a story about the interrelated imperatives of property, profit and settlement, which have underscored the construction of urban streets and concomitant projects of Aboriginal marginalisation in Melbourne.

If, as historian and critical theorist Patrick Wolfe has argued, ‘invasion is a structure, not an event’, then we can see the Hoddle grid as a thoroughly settler colonial structure, supporting profits of land and commerce that have mutually supported the lives of settlers and marginalised Aboriginal people.[5] Those of us who are concerned to decolonise our cities might, then, point our fingers at the apparently benign straight street and right angled corners of the grids we live in, and ask: Who benefits from this order?

[1] See Penelope Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers: Indigenous peoples and settlers in 19th Century Pacific Rim cities, 2010.

[2] Paul Carter, The Road to Botany Bay, 1987, 221.

[3] *Ngurungaeta is Woiworrung for Chief.

[4] See Robert Kenny, ‘Tricks or Treats? A case for Kulin knowing in Batman’s Treaty,’ 2008, 1-14.

[5] Patrick Wolfe, ‘Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native’, 2006, 338.

Nadia Rhook researches and lectures colonial history at La Trobe University. Her research on the urban politics of Chinese and South Asian settlement in late 19th Century Melbourne has been published in Postcolonial Studies and the Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. She is currently co-curating an exhibition, ‘Moving Tongues: language and difference in 1890s Melbourne’, to show at the Melbourne City Library in October 2016.

Pingback: Neoliberalism and the Structure of Settler Colonialism in a North American City | Global Urban History