The Conversations section of our blog seeks to foster critical exchange about the theoretical and methodological implications of bringing together global and urban history. The blog’s editors will occasionally interview scholars to discuss questions of global urban history, spanning across different regional and thematic concerns. For this post, we are thrilled to have spoken with Shane Ewen, Senior Lecturer in History at Leeds Beckett University. He is the author of What is Urban History? (Polity Press, 2015). He has written extensively about urban transnational history, urban governance, and environmental disasters. He is one of the editors of Urban History. He is also a member of the International Committee of the European Association for Urban History, one of the Board of Directors for the Urban History Association, and is on the Conference Steering Committee for the Urban History Group.

Shane Ewen

Question: During the past ten years, the growth of global history has also inspired historians of cities, who increasingly investigate the role of cities in empires, long-distance trade, and maritime networks. Urban historians have also shown a growing interest in how global connections manifested themselves in the local spaces that they study. Conversely, scholars of global history draw on urban history as a way to situate their studies in concrete locations. Concentrating on cities as nodal points, for instance, has allowed historians to render more tangible the elusiveness of the far-flung connections they are so interested in. Such a concrete spatial focus may thus not only provide more manageable units of analysis, but also prove to be an effective antidote to some reservations regarding global history. Indeed, Frederick Cooper’s warning about the “lumpiness” of global connections can be illustrated most vividly through urban history.

Even so, explicit combinations of the labels “urban history” and “global history” seem to remain rare—a surprising finding if one considers the two fields to be as congenial as outlined above. This scarcity also contrasts with proliferation of the prefix “global” in other established subfields of the discipline, as in “global intellectual history.” But our first question to the participants of our discussion should really be whether you agree at all with the diagnosis that global history and urban history have not often been coupled explicitly so far? And if so, do you find this surprising and where do you see the reasons for this? If you disagree, where do you see the most important precedents for combining the two?

Shane Ewen: This is a question that I  wrestled with whilst writing What is Urban History? and I am inclined to argue that urban and global history have been converging in recent years, especially if we are flexible in defining the field and method of inquiry. Indeed, given the parallels between urbanization and urban scholarship, it is hardly surprising that the two sub-fields have been moving ever closer, especially since more than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas. And much of the work that has accompanied this demographic surge has been alert to the importance of situating the city biography into a wider international, transnational, and comparative context. It might not be global in the strictest understanding of the term, but it is outward looking, especially in seeking the wider flows and circulations that connect cities into international and global networks of trade, governance, culture, and such like.

wrestled with whilst writing What is Urban History? and I am inclined to argue that urban and global history have been converging in recent years, especially if we are flexible in defining the field and method of inquiry. Indeed, given the parallels between urbanization and urban scholarship, it is hardly surprising that the two sub-fields have been moving ever closer, especially since more than half the world’s population now lives in urban areas. And much of the work that has accompanied this demographic surge has been alert to the importance of situating the city biography into a wider international, transnational, and comparative context. It might not be global in the strictest understanding of the term, but it is outward looking, especially in seeking the wider flows and circulations that connect cities into international and global networks of trade, governance, culture, and such like.

For example, in a recent book that I was involved with, Cities Beyond Borders: Comparative and Transnational Approaches to Urban History (2015), the editors, Nicolas Kenny and Rebecca Madgin, convincingly argue that, in a world of increasingly dense global connections, urban historians need to embrace comparison in their research. Indeed, our cities, as objects of analysis, are inherently comparative because they are the product of urban forces that come together in a material, environmental, organizational, and experiential sense.

Cities Beyond Borders grew out of a round table session that I participated in at the 2012 conference of the European Association for Urban History held in Prague. The panel was on “Comparative, Transnational and Globalised Perspectives on Urban History,” so it is interesting that the book title was tweaked to reflect the methodological themes that shaped the discussion during the session. The theme of the Lisbon conference as a whole was “Cities and Societies in Comparative Perspective” and the program reflected growing scholarly interest in seeking the connections between the European urban experience and the wider world. Indeed, it attracted a wide range of panels on non-European cities—tackling topics relevant to the history of European empires, the diffusion of urban planning models, European travel to Islamic cities, and South Asian perspectives on urban culture. The 2014 conference in Lisbon consciously continued this blossoming extra-European interest with the theme of “Cities in Europe – Cities in the World” and included sessions on topics such as the growth of municipal institutions, networks and experts in the twentieth century, and border cities in Europe, Asia, and America. We intend to continue these conversations at Helsinki in August. There has been a similarly noticeable shift towards an international focus in the Urban History Group’s annual conference in the UK: the most recent meeting, at Cambridge in March, included papers on global urban segregation and streets and neighborhoods in an imperial and trans-Atlantic context. If these conferences are a barometer for future published research, there are clear signs that urban historians are becoming more alert and responsive to the global connections between their city case studies.

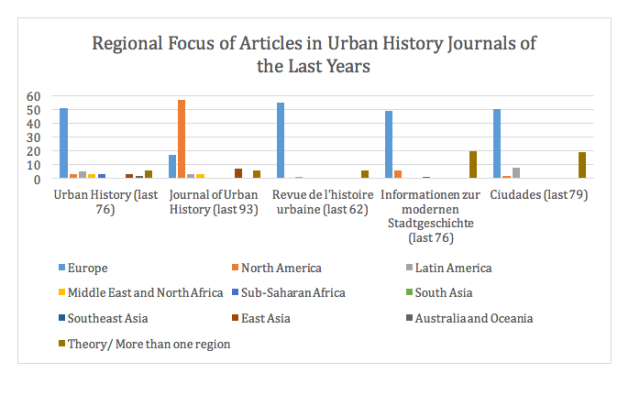

Much of what you say points to the long established links between urban and global history, even though social scientists may have stressed this earlier than historians did. Still, if one looks at urban history as a distinct field of study replete with its own journals and book series, beyond your own work one is hard pressed to find a great many examples of studies dealing with cities in more than one country or world region—and particularly work on the urban history of what today is called the Global South. As this graph suggests, urban historians seem to continue to focus mostly on U.S. and European cities. Do you think that this might represent a problem for global history, which usually comes alongside pleas to overcome conceptual and topical Eurocentrism? Is the very fact that between 1700 and 1930 most of the world’s largest cities were in Europe, North America, and East Asia an obstacle for combining urban with global history, so that histories of world regions whose populations mostly lived in the countryside during many centuries are neglected by urban history?

You’re certainly correct in saying that few urban histories have a truly global reach, especially monographs or single-authored journal articles. Those histories with a more or less global coverage tend to be edited collections, with multiple authors, which, when taken wholly, provide a broad geographical and temporal coverage. This was certainly the challenge that Pierre-Yves Saunier and I faced when putting together the contributors for our book, Another Global City: Historical Explorations into the Transnational Municipal Moment, 1850-2000. We were aware of a significant discrepancy between the global cities literature and the allegedly global reach of their studies, which tended to focus on those larger cities that were responsible for the production and flow of the majority of global capital. We were also obviously cognizant of the geographical limitations of the case study approach, which is prevalent within the field of urban history. Taken individually, our chapters offered little to a global understanding of the municipalization processes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but taken collectively we identified some common themes that united municipalities across the world. In particular, we mapped the various schematic waves of transnational municipalism—the informal, one-off transfers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; the formal organizational connections of the mid-twentieth century; and the dense, institutional and extra-institutional networks of the late twentieth century—which have proven to be of some significance with more recent studies.

The reason why few urban histories take a global coverage is due to the field’s dominant case study approach: the majority of studies still take the single “place in context” approach. This is part of urban history’s DNA, certainly in the U.K. and the U.S., where the foundational studies in the 1960s—by H.J. Dyos, Asa Briggs, Sam Bass Warner Jr., and others—all took individual cities as their main unit of analysis. But it was always their intention to go further than the local community by examining the relationship between their cities and the wider regional, national, and international context within which they emerged. As Dyos wrote in his “Agenda for urban historians,” published in 1968, urban history involved “the investigation of altogether broader historical processes and trends that completely transcend the life cycle and range of experiences of particular communities.”[1] What this meant in practice was that urban historians have tended to exemplify the detailed socio-economic, political, cultural, and environmental factors that shape their city; very few take a broad brushed approach towards surveying the urban experience more generally, preferring to leave this to social scientists.

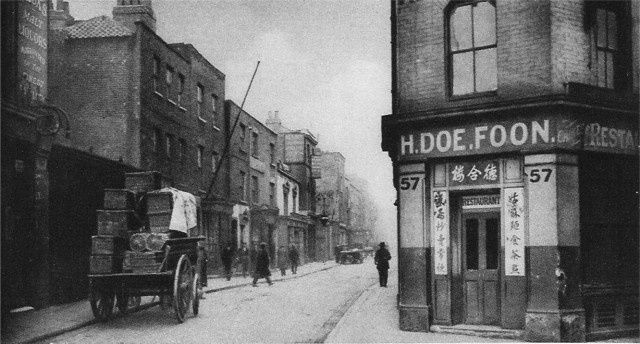

Limehouse Causeway, London, 1933

However, a growing number of historians take a comparative approach, and increasingly so by comparing cities across national, and even continental, borders. Good recent examples of these, which take an “urban problem” approach, include Carl Nightingale’s Segregation (2012) and Harold Platt’s Building the Urban Environment (2015). These are international comparative urban histories rather than integrated global urban histories per se, largely because they are still fundamentally about individual cities with their own unique regional and/or national histories, but I don’t see anything wrong with that.

This all points towards a challenge for urban historians, not least those of us who edit the journals included in your graph, who are keen to publish good original research on cities from the Global South as well as more transnational histories in general. We have been especially keen to broaden our geographical coverage at Urban History in recent years, certainly beyond its traditional U.K. focus, and our international editorial board reflects our interests in the Global South as well as our traditional heartlands. There’s certainly good scholarship out there—African history journals, for example, have published interesting articles that would not have been out of place in our journal—so the challenge is perhaps to convince those authors to publish with us. But it is also a challenge for those authors to map out an alternative approach to historicizing the urban experience away from western paradigms (and it is good to see scholars doing this via your blog site). I’d like to encourage those reading this to send their articles or shorter opinion pieces to the editors at Urban History.

Limehouse Causeway, East London’s Chinatown, 1927

Dovetailing with the wider trends in history over the last thirty years or so, practitioners of global history have identified in “methodological nationalism” their hereditary enemy. Yet, when speaking to urban historians, they might well be preaching to the converted in that urban history has never viewed the nation-state as its natural category of analysis. Can historians of cities learn anything new from global history? Conversely, what exactly can global history learn from urban history—especially seeing that global history is a field reluctant to predefine its spatial unit of analysis, whereas urban history has in this pre-definition its very raison d’être?

Urban history and global history are not mutually exclusive sub-fields. As you say, they both share common traits in seeking to go beyond “methodological nationalism” by focusing on alternative spaces ranging from the town to the supranational institution. This opens both fields up to interdisciplinarity, seeking answers (and often questions) from other disciplines, especially in the social sciences. Urban history, Jim Dyos wrote in 1974, is “not a single discipline in the accepted sense but a field in which many disciplines converge, or at any rate are drawn upon.”[2] And we see this convergence in practice at the various international urban history conferences that I mentioned earlier, which regularly attract geographers, planners and architects as well as urban historians (and not forgetting those historians of cities who predominantly define themselves as social, economic, or cultural historians).

Now, interdisciplinarity can be fruitful, so long as social scientists also think historically, which often they don’t, as we found when doing the research for Another Global City. However, the growing trend towards historicizing the recent past within the urban historiography—and here I am referring to the post-war city (or, in the U.K., post-1950, which picks up following the end date of the three-volume Cambridge Urban History of Britain)—has brought historians and social scientists into contact, not entirely successfully yet. And given the social scientist’s propensity for taking the problem-solving approach towards their research, for working comfortably with theory, for thinking “big,” and for extrapolating grand conclusions from their data, there is much work ahead for urban historians in thinking about the bigger picture around their case studies. And it is here that we can learn much from global history, in knitting together our local studies into something that is more than the sum of its parts, and in saying something more general about the nature of urban life. One of the few urban historians who has done this is Charles Tilly, who argued that comparison, over long periods of time as well as across space, gives the urban historian the tools to answer the bigger questions in academic scholarship: How is urban society organized? Who wields power in the cities and how do they manage this? How is this resisted and challenged by less powerful groups? To what extent is there a universal urban culture?—and so on.[3]

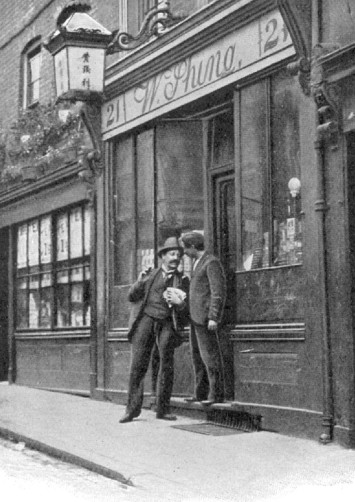

Chinese Shop on Limehouse Causeway, 1927

What urban history offers the global historian, on the other hand, is a more nuanced perspective on the world, through a focus on the local place—it can shed light on the reasons behind a particular place’s significance in global networks, or explain its marginality. This is, as you say, our raison d’être, but it comes with our training as postgraduates. It helps us understand why some cities are orthogenetic, being focused on their local or regional relationships, while others, in being plugged into vast international networks, are heterogenetic in outlook.[4] By digging deep into the archives of a particular place, the researcher is able to identify and trace the wider connections—one-off or part of a more sustained network—between their town or city and the wider urban community. The case study approach enables the urban historian to connect their findings with the wider scholarship in global and transnational history, to identify commonalities in urban experience, and to identify differences, as well as critically account for them. It helps to capture what makes a town or city unique, whether that stems from its economic structure, demography, political regime, cultural values, social institutions, or spatial form. The case study approach, whether singularly or as part of a comparison, thus helps to ground the global studies literature in concrete places, reminding scholars that no two places are the same.

[1] H.J. Dyos, „Agenda for Urban Historians,“ in idem, ed., The Study of Urban History: The Proceedings of an International Round-Table Conference of the Urban History Group at Gilbert Murray Hall, University of Leicester, on 23-26 September 1966 (Edward Arnold, 1968), 7.

[2] H. J. Dyos, “Editorial,” Urban History Yearbook 1 (1974): 5.

[3] Charles Tilly, “What Good is Urban History?,” Journal of Urban History, 22 (1996), 702-719.

[4] These typologies of urban places are explored in more detail in Lynn Hollen Lees and Andrew Lees, Cities and the Making of Modern Europe, 1750-1914 (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Editor’s note: The table “Regional Focus of Articles in Urban History Journals of the Last Years” has been edited to correct minor inaccuracies. 26/09/2016

Pingback: This Week’s Top Picks in Imperial & Global History – Imperial & Global Forum

Pingback: Book Review: Shane Ewen, What is Urban History? – history.city

Pingback: “The ‘Urban Question’ is Now at the Center of Intellectual Life”: A Conversation with Rosemary Wakeman | Global Urban History