By Rasmus Christian Elling, University of Copenhagen

The Iranian Revolution, most historians argue, was an urban phenomenon in which mass demonstrations in major cities led to the spectacular downfall of the shah in 1979. In addition to Ayatollah Khomeini’s politicized Shiite-Islamic discourse, it is further argued, popular revolutionary resolve was prefigured specifically by Marxist urban guerrillas. But what was urban about these guerrillas?

In trying to answer this question, I recently contributed to a new edited volume on Global 1979: Geographies and Histories of the Iranian Revolution. In this blogpost, I will recap the main arguments of that chapter and then demonstrate why this research matters for global urban history. Briefly put, I believe expanding urban analysis beyond the Euro-American sphere to places like Iran can help us understand global relativity in terms of simultaneity rather than only through transnational movement, circulation or traveling theory.

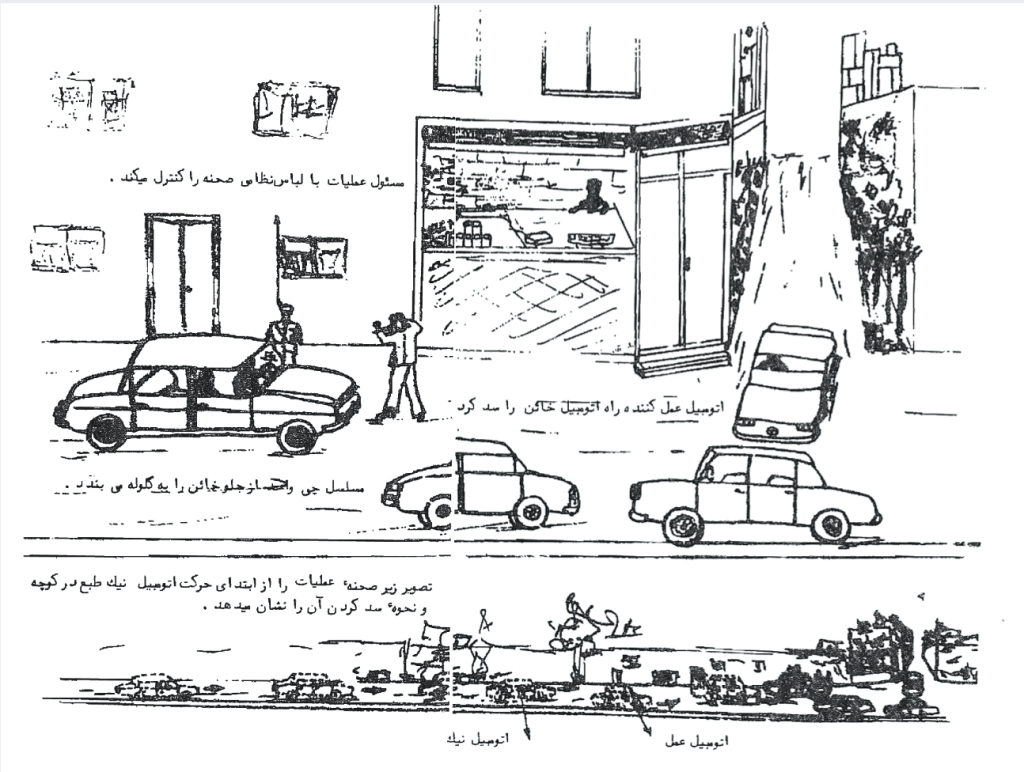

In my research, I examined materials pertaining to the history of the Sāzmān-e charik-hā-ye fadā‘i-ye khalq (The People’s Self-Sacrifizing Guerillas’ Organization, henceforth the Fadā‘is). The Fadā‘is launched an armed insurrection in 1971, striking police stations, international hotels, banks and a range of symbols of state pride in order to erode the image of an unassailable, all-seeing state. I have argued that four points will make us understand the Fadā‘is as an urban phenomenon:

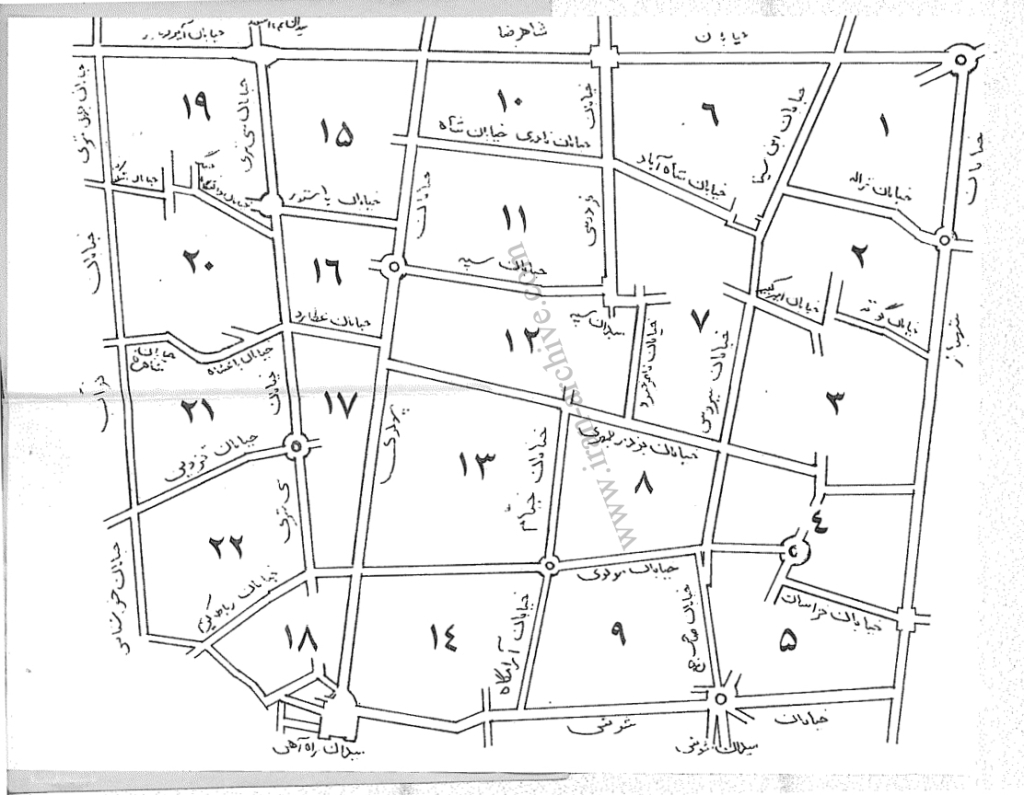

First, I’ve shown how Iran’s rapid urbanization in the 1960s and 1970s shaped Fadā‘i thinking and brought about material conditions conducive for underground militant activism. Secondly, I’ve explored how urbanization, in both socio-economic and cultural terms, was treated analytically in the Fadā‘is’ prolific writings. Third, I’ve demonstrated how the Fadā‘is developed a so-called “guerrilla urbanology” (shahr-shenāsi-ye chariki): a subversive epistemology of the urban as a setting and resource for armed propaganda under police state conditions. And finally, I’ve analyzed the fieldwork reports of clandestine Fadā‘i cadres infiltrating Tehran’s shantytowns in order to investigate the urban subproletariat as a possible agent of revolutionary change.

What struck me again and again during this research is how the Fadāi’s connected urban questions in Iran – about housing, demographic change, land ownership, the ‘urbanization of consciousness’ etc. – to global questions about imperialism, capitalism, socialism.

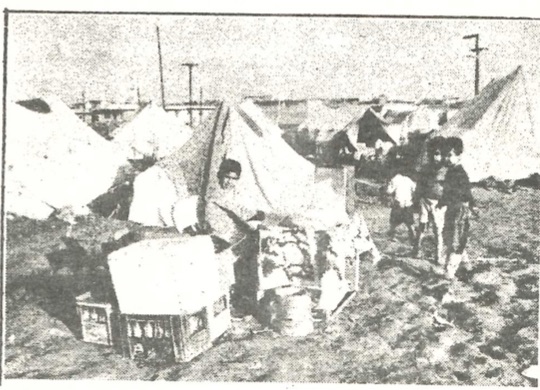

An example of this can be found in the fifth edition of the clandestine Fadā‘i periodical Nabard-e Khalq (“The People’s Struggle”) from September-October 1977 under the headline “A Case of Mohammad-Reza Shah’s Anti-People Dictatorship’s Violations Against the Rights of the Motherland’s Toilers.” The report describes the travails of inhabitants in a shantytown located, ironically, in the part of Tehran that saw some of the earliest modern urban development, namely Tehrān-Villā and Shahrārā. Here, urban toilers (zahmatkeshān-e shahri) languished in tents, sheds and makeshift huts, struggling to survive precarity without basic amenities, surrounded by toxic garbage disposals and constantly threatened by authorities’ violent attempts at eviction.

The Fadā‘is place this case in a larger political economic perspective. The toilers were rural migrants uprooted from villages by landowner despotism following the shah’s so-called White Revolution of 1963, the land reforms of which Fadā‘is interpreted as comprador capitalist policy dictated by the shah’s American superiors. Joining the “reserve army of labor” in sprawling slums, the migrants soon found themselves under increasing pressure from state-led gentrification, systematic extortion and, when authorities failed to expulse them, measures to segregate and cordon them off from the surrounding prosperity.

In this case, that included the building of a wall to conceal the squalor from visiting international dignitaries during the 1971 celebrations of 2,500 years of monarchy. In the run-up to the 1976 Asian Football Federation’s Asian Cup, authorities again tried to evict the inhabitants. By 1977, the local fire station had a water cannon permanently pointed at one of the shantytowns in an attempt to force inhabitants off the precious land.

With reference to official international events and relations, the Fadā‘is connected the dispossession of urban toilers to broader structural issues of global capitalism. But they also documented resistance: from passive non-compliance and acts of solidarity and mutual aid to sabotage and even collective violent resistance. The Fadā‘is believed that through everyday struggle, the urban toilers “come to realize, to a certain extent, their combined collective power.” This self-empowering realization appeared to be exactly that seed of revolution the Fadā‘is had been looking for when they took up work in factories or visited shantytowns.

In other words, the Fadā‘is saw the city as both the scene for authoritarian repression entangled in global power relations – and as the site of emerging emancipatory potential. The city was both home to a pacified or collaborationist bourgeoisie culture entangled with global capitalism and to a rebellious counterculture, the forefront of which were the guerrillas staging skirmishes in what Fadā‘i theoretician Bizhan Jazani called “a forest of humans.” And the Fadā‘is were not alone with this analysis.

Another prominent guerrilla organization, the Mojāhedin-e Khalq (MEK), also placed urban struggles centrally but within an eclectic synthesis of Marxism and political Islam. Like the Fadā‘is, the MEK attempted to embed itself with the toiling classes, producing pamphlets and quasi-ethnographic field reports. Some of this material was translated into English and published as Cities in the Clutches of Imperialism in 1981 — just when MEK, along with all other Left-leaning forces, were about to be violently expulsed from the political scene by their erstwhile Khomeinist allies.

The historical argument in this pamphlet is that as opposed to British imperialism, which had propped up rural feudalism in order to plunder Iran’s natural resources, the rise of American imperialism after the CIA/MI6-supported coup against Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq in 1953 aimed to develop Iran as a comprador capitalist society by replacing feudalism with urban-centered capital accumulation around an urban-based bourgeoisie. The latter would act as a dumping ground for the West’s overproduction of goods.

The imperialist-aligned policy was to keep prices low for Iranian agricultural products and wages low for the rural masses producing them. With the drastic expansion of mechanized agro-businesses and parasitical banks, and further bolstered by official media campaigns “laden with glossy references to the attractions of city life,” villagers were soon “flocking towards the bright lights” – only to end up as cheap, exploited or unemployed labor in the shantytowns. The pamphlet zooms in on these “dark corners of our cities” – and then places them in a global perspective:

“Tenements or hovels, the decayed inner city or the ragged shantytowns, favelas or bidonvilles on the outskirts, are a prominent feature of London, Paris, New York, Cairo, Tehran (as well as capitals throughout the exploited world of Asia, Africa and Latin America: Rio, Kinshasa, Bangkok, Manila, etc. etc.)”

The text moves through ethnographic observations and quotes from slumdwellers but constantly returns to the “satanic domination of imperialism.” The pamphlet, for example, outlines the plight of one brick kiln worker, typical of the rural migrants trapped in impoverishment:

“After a lifetime of hard labor, he and his family have only a small room as their living quarters, granted by the owner of the kilns. This is a glowing testimony to the 35 years of dictatorial misrule, decades of domination by world-devouring imperialism, and fifteen years of control by the comprador bourgeoisie – a by-product of the Pahlavi land reform which was decreed by the dictator to satisfy the interests of his American bosses.”

While the Fadā‘is would explain this with a Marxist vocabulary familiar around the world, the MEK sprinkled the text with references to the Quran and the Shiite Imams. This indicated an important point of divergence that would also, not incidentally, come to mar the afterlife of the revolution. Whereas the Fadā‘is tended to treat religion as superstition to be wiped out of the superstructure through ideological education, the MEK tried to merge the universals of Marxism and Shiism as re-interpreted by new religious thinkers such as Ali Shariati. For the MEK, the doctrine of towhid (“divine integration”) dictated a combined struggle against capitalism/imperialism and against Satan and idolatry.

At the end of the day, both groups would lose the grip on the revolution they had helped create. By 1979, the guerrillas were exhausted and decimated by a decade of repression, marred by infighting, sectarianism and authoritarian tendencies, and then divided over the issue of loyalty to Khomeini. They were simply unable to turn, at a crucial time, their widespread popularity in the urban academic middle classes into a united front that could resist the theocratic forces. Nonetheless, their legacy tangibly impacted the post-revolutionary Islamic Republic, not only in an official anti-imperialist stance but also in rhetoric about the rights of the “downtrodden masses.”

The revolutionaries’ urban analysis – arguably simplistic in its worldview but often deep and rich in ethnographic detail and historical arguments – was in fact cutting-edge critical thinking at a time when censorship and repression had left academia, journalism and public intellectualism more or less stifled and stale. There is a case to be made, in other words, that despite its overt ideological framing and bias, the textual production of revolutionary guerrillas can function as valuable secondary source for understanding Iran in the 1970s.

In a global perspective, there are also interesting historical questions to be raised. I argue that with urban analysis, groups such as the Fadā‘is and the MEK not only sought to raise awareness of how everyday life was shaped by the contradictions of global capitalism and imperialist exploitation. They also aimed to bridge the universalist prescriptions of Marxist theory with the local, particular conditions of a national liberation struggle in Iran. As such, urban and rural facts were sometimes used to debate and position this struggle vis-à-vis other experiences with revolution and resistance, be these Russian, Chinese, Cuban, Vietnamese or South American — and to then settle on what the revolutionaries perceived to be an appropriate Iran-specific praxis.

However, instead of boiling this relativity down to Iranian revolutionaries simply “responding” to world events, it can be thought of as a question of temporality. Just when a certain thinker in Paris was prompted by the Maoist idea that cities of the Global South were surrounded by hinterlands teeming with revolution to think about the opposite – namely, that a planet covered with urban tissue would center “the right to the city” as a global “cry and a demand” – so were leftist thinkers in Tehran noticing, already in the late 1960s, how “the urban” had overflown the conceptual confines of “the city,” blurring social, cultural and material divides with its pushes and pulls.

In other words, before Lefebvre had published his seminal texts about urban revolution, Marxists in Iran were going against fashionable Maoist currents on the Third-Worldist scene in arguing that urbanization would eventually herald a new phase in the national liberation struggle. This, it should be emphasized, was before they read Carlos Marighella’s Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla or heard about the shift in Latin America from rural foco-style rebellions to urban insurrection.

This, to me, shows that rather than thinking about the transnational routes through which ideas circulate or “trickle down” across the globe, we also need to think about the simultaneity with which new ideas and practices emerge when prompted by global processes such as urbanization. The global and the urban are co-constitutive and produce local particularities to be explored and exploited. Rather than mere “recipients” or “readers” of global urban analyses of revolution, the urban guerrillas of 1970s Iran were in fact co-authors.

Rasmus Christian Elling is an Associate Professor at the Department for Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen (Denmark), where he teaches Middle East Studies and Cross-Cultural Studies as well as Global Urban Studies summer schools. With a PhD in Iranian Studies, his research centers on the urban and social history of modern Iran. See his latest publications here.