By Jeffrey C. Guarneri, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Japan’s interwar period (1918-1941) was a time of profound changes in Japan’s ports of international trade, cities which simultaneously helped to drive Japan’s rise to world economic power status during World War I and became highly vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the global economy thereafter. The historiography on Japan’s interwar period posits this vulnerability, and the many economic crises that laid it bare, as among several catalysts for Japan’s descent into a “dark valley” of nationalism, international isolation, economic autarky, and war in the 1930s. However, when viewed from the perspective of Japan’s commercial ports, whose fortunes depended on their country’s continued membership in the liberal international order even amidst strained circumstances, we see that local boosters (government officials, businessmen, local media, and educators) in these cities doubled down on official narratives for their cities which drew on their respective international maritime networks to define their communities in global terms, rather than bending inexorably toward militarism and a departure from the international community.

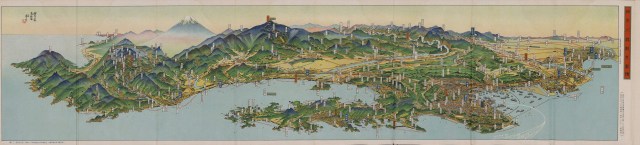

Bird’s-eye-view map Kanagawa Prefecture (1934)

Perhaps most emblematic of these efforts to promote such global visions of Japan’s ports were the chōkanzu, or “bird’s-eye-view maps,” that Japan’s municipal governments and chambers of commerce commissioned in large numbers in the 1920s and 1930s. These maps belonged to a genre whose traditions stretched back hundreds of years. What had changed by the interwar period was the extent to which this newer wave of chōkanzu was intended to serve as a consumable, mass-produced promotional tool that would draw in tourists, advertise these ports as industrial or commercial hubs, or otherwise map their respective places in global geographies of trade, tourism, and transportation. Affordable and compact, colorful and packed with textual glosses outlining the history and famous sights of the cities they depicted, the maps presented these entrepôts as places where Japanese people could experience their empire’s global presence without leaving the country, or where foreign visitors could venture out into Japan from comfortable enclaves of Euro-American food, fashion, and architecture.

In addition to having an outside audience in mind when creating such maps, the local boosters promoting this logic of global citizenship were also active in crafting official, city-sanctioned narratives that attempted to make international trade the bedrock of local civic identity. This, in turn, was achieved by presenting these harbors as global ports whose histories had been made by years of international commercial and cultural engagement, or as locales whose place in national narratives was defined by their role as intermediaries between Japan and the rest of the world. Three chōkanzu are particularly illustrative of this trend: Kanagawa Prefecture (1934), which featured the city of Yokohama in eastern Japan; International Port City Tsuruga (1932), which featured the port of Tsuruga on Japan’s west coast; and Picturesque Nagasaki (1934), which featured the old port of Nagasaki in southwestern Japan.

Bird’s-eye-view map International Port City Tsuruga (1932)

As the leading representatives of the business communities (especially import-export firms, industrial manufacturing, and tourism) and local officialdom (elected politicians, bureaucrats, and educators) in Yokohama, Tsuruga, and Nagasaki, the groups that commissioned these chōkanzu had a vested interest in sustaining their ports’ overseas commercial ties and “selling” the idea of global belonging to the local citizenry in order to create buy-in for economic development policies that sustained those connections through international trade, tourism, and industrial manufacturing. These local elites also consistently betrayed considerable pride, in both public and private, in the prestige accrued to their respective cities by virtue of their overseas connections. The chōkanzu in these three ports and the official civic narratives they captured were consequently no mere celebrations of the material benefits of international trade. Rather, they were also used to celebrate these harbors as above and apart from other Japanese ports whose economic networks extended no further than the bounds of Japan’s empire.

Map indicating the location of the three port cities.

In Kanagawa Prefecture, Yokohama was touted as the “gateway to the imperial capital” of Tokyo (located nearby and due north), “the place through which all travelers must pass on their way to the capital” and gatekeeper between the heart of the empire and the world in which Japan had become an economic and military power. International Port City Tsuruga, commissioned by the municipal government and Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Tsuruga, hailed the port as “gateway to the world highway” and critical node on the “one road from Europe to Asia” stretching all the way to London via the Sea of Japan and Trans-Siberian Railroad. Picturesque Nagasaki’s emphasis on links to ports in China and the South Pacific reflected Nagasaki’s closer proximity to mainland China than to Tokyo as well as its overwhelming reliance on Shanghai for its seaborne trade, all the while touting the port’s long history as “Japan’s sole open port” during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and “birthplace of modern Japan.”

The international networks that featured so prominently in these promotional maps equaled and often displaced domestic referents in laying out official, city-sanctioned visual narratives of the ports they depicted. Each played with space and representation to variously prioritize maritime routes that connected these cities to imperial metropoles overseas, or demonstrate how these ports directly connected Japan’s overseas trade partners to its hinterlands. The Yokohama chōkanzu presented here, like other such maps of the city, shows rays emanating from the port and across the Pacific Ocean “to America,” “to Europe,” and “to Asia,” defining Yokohama in terms of these overseas locales by sea as much as its place at the threshold of Japan’s political and economic center. Tsuruga chōkanzu often excluded large swaths of the Japanese archipelago from view in favor of giving ample space to its maritime routes crossing the Sea of Japan and railway connections spanning Eurasia, which Tsuruga’s boosters claimed made their harbor part of a singular space running from Tokyo to Europe’s greatest metropoles. Chōkanzu depicting Nagasaki consistently tucked the rest of the archipelago into a corner of the map, concealing nearly all but the island of Kyushu while instead drawing viewers’ attention to white lines stark against the ocean blue of the South China Sea and extending toward the horizon to directly connect Nagasaki to the global commercial hub of Shanghai.

Bird’s-eye-view map Picturesque Nagasaki (1934)

However, beneath the forcefulness with which local boosters promoted this globality through chōkanzu, these objects can also be interpreted as texts informed by concerns over the fragility of these ports’ overseas commercial relationships in the turbulent interwar years, and as attempts to reconcile previously stable overseas connections with an increasingly unstable domestic and international situation in the present. For Yokohama, a devastating earthquake in 1923 accelerated a bleeding off of its overseas trade to rivals Kobe and Osaka, while plans to construct a port of foreign trade at Tokyo in the 1930s dovetailed with the collapse of Yokohama’s chief export market (the United States) to pose what local boosters deemed an existential threat to their port’s economy. Tsuruga’s rapid growth in the early twentieth century depended on stable trade with Europe via Russia and Manchuria, conditions that were frequently upset by epoch-making events like the October Revolution in Russia, the collapse in global demand wrought by the Great Depression, and Japan’s worsening international trade and political relations following its 1931 invasion of Manchuria. Nagasaki, meanwhile, had been so marginalized within Japan’s international commerce by the 1930s that its overseas trade was all-but reduced to China, leading local boosters to prioritize their connections to Chinese markets at the same time that these markets were hotbeds of anti-Japanese boycotts prompted by Japan’s military aggression on the mainland.

To boosters in these cities, nothing could sever their ports from the Japanese nation-state. However, the myriad trade, fiscal, and geopolitical crises of the interwar years and rising nationalism in Japan stoked fears among these boosters that the instability of the present threatened to sever their ports from the world trade on which they depended, and which these business and political elites felt defined their cities.

Even in the face of rampant jingoism at home after 1931 and Japan’s increasing diplomatic isolation by the late 1930s, the local elites who sought to keep official discourse in these ports anchored to their ports’ global connectivity recognized that abandoning the liberal international order in favor of imperial autarky was something done at their own peril. Boosters in all three ports were well aware that their continued exercise of economic power on the international scene overwhelmingly depended on trade with other empires or places under multi-imperial control (such as Shanghai) in addition to Japan’s position as a major imperial power in the Asia-Pacific region. Consequently, they went to great lengths to construe the projection of imperial power and membership in a world-wide commercial network not as mutually exclusive of one another, but rather as deeply intertwined preconditions for how these ports could remain active agents of global commerce.

In the case of Tsuruga, whose close proximity to Northeast China meant that it stood to directly benefit from the establishment of a puppet state in Manchuria, commentators from within and without the port responded to fears about the international opprobrium greeting Japan by claiming that increased traffic to Manchuria through Tsuruga would enhance, but not diminish or replace, the port’s connectivity to European metropoles and markets. In the case of Yokohama and Nagasaki, for whom an expected “Manchuria boom” failed to materialize to the extent it did for Kobe and Osaka, the emphasis ultimately remained on extra-imperial projections of economic power into markets in both sovereign states and Euro-American colonies.

By publishing chōkanzu and using them as promotional tools, the civic boosters who commissioned these maps actively promoted their ports as more than just “cities of Japan,” but instead “cities of the world” whose routes stretched from Tokyo to London, to the cosmopolitan hub of Shanghai, or across the Pacific to San Francisco and Vancouver. This “global sense of place” was shaped by these ports’ role of “channeling mobilities” of people, goods, and money throughout the world. Rather than reducing these cities to where they belonged within the nation-state and empire, the chōkanzu of the interwar decades demonstrate that these ports’ roles in an international division of economic labor remained a key element in shaping urban identities in some of Japan’s most globally-connected places, even amidst the turbulence of the 1930s.

Jeffrey C. Guarneri is a PhD candidate in Modern Japanese History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.