The Metro in Santiago, Chile, has an unlikely history. It opened to the public in September 1975, two years after the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende’s socialist government, while the country was reeling from the human rights abuses and political persecution that followed in the wake of the coup. The military dictatorship, led by General Augusto Pinochet, celebrated the new transportation system as a marvel of technology and development, as proof of what could be accomplished under authoritarian rule. The Metro was a symbol of the regime’s “new style” of governing, one minister proudly proclaimed: “What is happening today in the Metro is happening in Chile.”

Metro construction on Line 1, circa 1972. See the Santiago Nostálgico Flickr account for this and other historical photos of the Metro.

Yet the project had been born a decade earlier, in the 1960s, and had advanced, to a significant degree, during Allende’s socialist revolution. It was a product not only of the dictatorship, but also of its predecessors and political enemies. Even as the military regime axed other major infrastructure projects—such as housing blocks, a hospital, and an innovative cybernetics program—the Metro lived on. Just as remarkably, the system remained owned and operated by the state, despite economic turmoil and the embrace of radical free-market policies in the 1970s. The Metro’s surprising survival raises a number of questions: What ensured its success? How did it reshape the city? And what can its history tell us about the intersection between global and urban history in Latin America?

I pursue these questions in my dissertation research and manuscript in progress, provisionally titled Vehicle of Progress: The Santiago Metro and the Construction of Democracy and Dictatorship in Chile.Rather than sum up my answers here, I instead wish to focus on one element: the project’s origins, and how they reveal the conjuncture of local and global forces that shaped the early years of the Metro, which was officially founded in 1968. Indeed, much of the Metro’s success can be explained by its fusion of national visions of progress, rooted in decades of research by Chilean engineers and urbanists, with long-term international funding and collaboration. Chilean experts worked closely with engineers from SOFRETU (Société française d’études et de réalisations de transports urbains), a French organization that helped build metros around the world starting in the 1960s. Notably, SOFRETU collaborated on the subways in Montréal, Mexico City, and Rio de Janeiro, which opened in 1966, 1969, and 1979, respectively. The Santiago subway was also part of a global boom in metro-building around this time, with many systems—including in rapidly-urbanizing Latin America—inaugurated between the late 1960s and early 1980s.

Before the French entered the scene, however, the Santiago Metro had a deeper local history. Since at least the 1920s, Chilean engineers had argued that Santiago needed a subway. Like cities throughout Latin America, Santiago exploded in size in the early- and mid-twentieth century as rural workers moved to the capital in search of a better life. The vast majority of residents relied on public transit, which typically meant a long ride on an overcrowded, poorly maintained bus. Urban transportation was not only a technical problem, but also a sensitive social and political issue; this was most dramatically demonstrated in 1949 and again in 1957, when fare hikes sparked mass protests and riots.

Repeated proposals for a subway in the 1940s and 1950s failed to gain traction, however. One of the biggest hurdles, not surprisingly, was a chronic shortage of financing. But several crucial factors came together in the 1960s to move the project beyond studies and blueprints. One of these was the rise of Juan Parrochia, a Chilean urbanist who had trained in Belgium and France and traveled throughout the world in the 1950s. He returned to Chile intent on remaking Santiago’s metropolitan transportation system, which he conceived as an unbreakable trilogy: he envisioned the future Metro as the city’s backbone, complemented by roadways and buses. He was aided by the election in 1964 of Eduardo Frei Montalva, a Christian Democrat and reformer who vowed to make the Metro a reality.

The metro project, pushed by Parrochia and Frei’s officials in the Ministry of Public Works, responded to local needs and the perception that an urban transportation crisis was looming. But it took international financing to secure the project’s future. Many countries competed for the metro contract, including Sweden, Japan, Canada, and the United States. But France emerged in the lead. SOFRETU, a subsidiary of the Paris transit authority, was rising to prominence as a global leader in metro expertise and technology. Engineers from SOFRETU had recently helped launch construction on the metros in Montréal and Mexico City, which gave them an edge in their negotiations with Chilean officials. Like the Santiago Metro, these systems used rubber tires, an innovation that was touted for providing a smooth, quiet ride. French prestige and style were also selling points, as evidenced by a 1971 advertisement for SOFRETU in Life magazine.

Life magazine advertisement for SOFRETU, which helped build metros around the world. Another page of the same ad reads “Métros for export.” Source: Life,May 7, 1971, Google Books.

Map of SOFRETU’s global network, 1983. Source: Alain Jeux, “ L’expérience de SOFRETU et de la R.A.T.P. dans le domaine du transfert de savoir-faire,” Revue générale des chemins de fer 102 (1983).

The collaboration between Chilean and French metro experts was strengthened by the geopolitical context in the late 1960s. Frei’s government had famously sought a “Revolution in Liberty,” a third way between capitalism and Communism that initially attracted significant U.S. support. However, U.S. aid had waned by the end of the decade, while the Chilean government was desperate for further resources to support its reform program. Into this gap stepped France, which, under Charles de Gaulle, expressed affinity with Frei’s independent diplomatic stance and was eager to promote French interests in the region. By offering major loans for the metro project, most of which went to finance the imported rolling stock, France secured its role in the project and enlarged the market for French rail manufacturers. This relationship lasted long after Frei: loans continued during the Allende government (1970–1973), the Pinochet regime (1973–1989), and the democratic Concertación period (1990–2010). Over the years, French financing was also complemented by significant sums from the Chilean national budget. Beyond its price tag, the project’s enormous scope and impact on the city—socially, culturally, and politically—meant that its path continued to be contested, long after the first line opened in 1975.

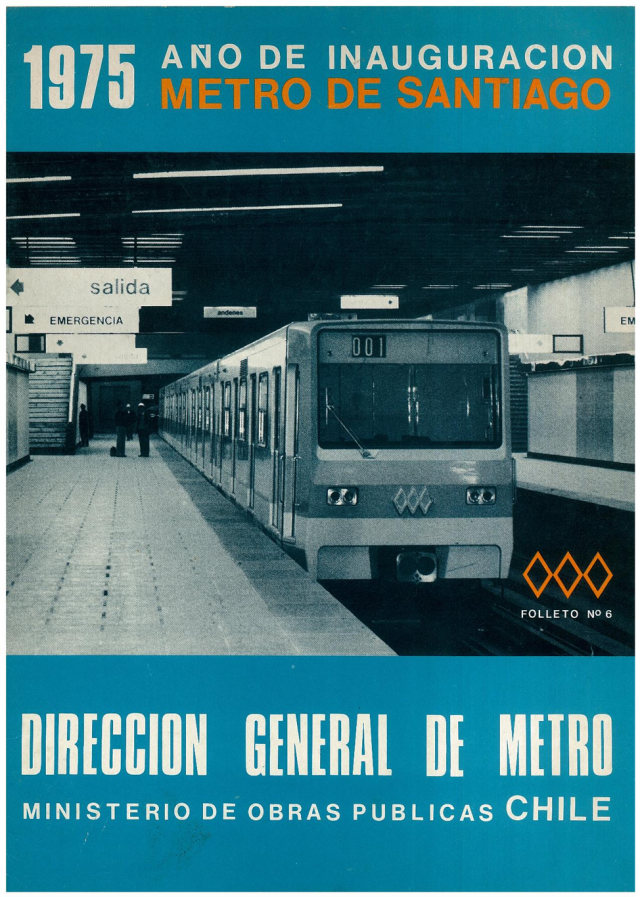

Pamphlet marking the inauguration of the Santiago Metro, 1975.

Today, the Santiago Metro has indeed become the backbone of the metropolitan area, carrying over two million people per day over six lines, with a new line slated to open in 2018. Because it is so essential to the city’s functioning, it is tempting to see the Metro as inevitable or transcendent, as the necessary response to a growing metropolis. But in fact, its path was highly uncertain and contingent, shaped by local urban growth patterns, the work of Juan Parrochia and his support from Frei, Chilean visions of progress and development, and—not least—the availability of French aid. The project was simultaneously rooted in local needs identified through decades of research by Chilean experts, as well the aspiration to join the elite ranks of cities that boasted a metropolitano.

Andra B. Chastain completed her PhD in Latin American History at Yale University in 2018. Her research focuses on urban history and the built environment, the history of technology, and the Cold War in Latin America. She will join Washington State University Vancouver as Assistant Professor of History in the fall of 2018.