By Daniel Knorr, University of Chicago

The “global turn” in historical studies is a recent phenomenon, but global comparisons have long been foundational in the study of Chinese cities. Max Weber framed this comparison as decisively negative in The City, contrasting the European experience – characterized by economically vibrant and politically autonomous cities – with that of China, which, in the ostensible absence of these characteristics, he claimed lacked true cities. William Rowe’s repudiation of Weber in his 1984 and 1989 books on Hankou (Hankow) epitomized both growing empirical understanding of Chinese cities and an increasing orientation towards what Paul Cohen termed “China-centered” history, which rejected orientalist assumptions about China’s history as static and incompatible with modernity. This “China-centered” approach by no means entirely eschewed comparative perspectives, though. Rowe’s own contributions to the debate about public sphere/civil society in China as well as the “sprouts of capitalism” discourse among Chinese historians testified to the prevailing interest in placing Chinese cities in a global framework. Some thirty years later – now in the context of an interest in global connections that has swept through all fields of historical inquiry – historians of China still confront the challenge of simultaneously explaining the unique aspects of the country’s history and staking a claim for the global relevance and connectiveness of our research.

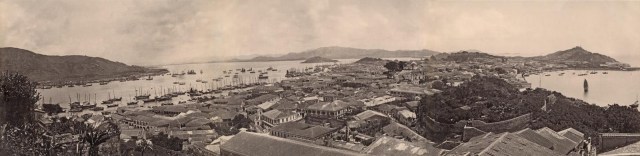

Nineteenth-Century View of Macau

In that spirit, I, along with Professors Liu Jiafeng and Ma Guang co-organized a workshop on the theme of Chinese Cities in World History at Shandong University on May 19-21. Our workshop included thirteen presentations organized into four panels, and a keynote lecture. The presenters themselves represented a diverse cross-section of academia, including scholars based in the U.S., Canada, mainland China, France, Hong Kong, and Macau.

The call for papers included four suggested areas of inquiry. One was broadly theoretical: how global comparisons have shaped approaches to theorizing Chinese cities. Two raised more specific empirical questions: the utility of imperialism and modernity as frameworks for studying urban history in China and how to situate a variety of Chinese cities (besides cosmopolitan centers) into a study of global history. We also proposed a discussion of methodological issues that arise at the intersections of Chinese, global, and urban history, such as the need for multi-archival research and the possibilities afforded by digital tools and source bases.

Participants at the Chinese Cities in World History Workshop

Perhaps the biggest surprise was the chronological breadth of the submissions we received. Because global urban history, like much of global history, often focuses on the modern era, I anticipated that scholars researching early modern and modern China would be most likely to be drawn to our workshop. However, we also received high-quality proposals for presentations about earlier periods of China’s history. To begin our workshop, we paired two of these papers, by Gwen Bennett and Chin-Yin Tseng with another, by Plácido González Martínez, that had a contemporary focus. Although these papers ran the gamut of disciplinary and chronological perspectives, they anticipated the presentations to come by underscoring the tenuous nature of the concept of a “Chinese city.” On the one hand, this term is useful for highlighting more or less distinctively Chinese characteristics. One example was how contemporary Chinese approaches to “heritage” emphasize restoration over preservation. On the other hand, however, scholars distill these characteristics from the confluence of diverse agents, activities, and interests that have constituted both historical cases of Chinese cities and the contemporary study of them. This over-determination of Chinese cities makes it impossible to posit a top-down definition of the Chinese city, not only because we need to take into account factors “from below,” but also because the “top” itself has been historically variable.

This view of Chinese cities – as products of diverse sets of actors and not simply features of the traditional Chinese state – reflects the scholarly turn mentioned at the outset of this post. Nevertheless, our conference showed that the repudiation of a Weberian view of Chinese cities and the growing interest in studying Chinese cities from a global perspective has by no means led scholars down a path of embracing a social history from below at the expense of the state. In fact, the state loomed large in our discussions. No fewer than six national/imperial capitals – Pingcheng, Chang’an, Kaifeng, Nanjing, Chongqing, and Beijing – were the focus of presentations, and the political importance of Jinan and Tianjin was cited as a crucial element in their respective histories as well. State and church also played a central role in presentations on colonial enclaves in Shanghai and Macau.

Dr. Lee Pui Tak Delivers the Keynote Presentation

On face, this preoccupation with the state appears out of step with developments in the field of Chinese history as well as the emphasis in global history on de-centering the nation-state as a unit of analysis. However, at the workshop we observed that ways of talking about the state have, indeed, shifted. In particular, the conventional dyad of state and society was noticeably absent from much of the discussion. Luo Xiaoxiang addressed this problem directly in her presentation about the role of Nanjing’s political heritage in late imperial literary discourse about the local character of the city. Highlighting the shortcomings of the state-society framework, she argued instead for understanding state and city as mutually constituted.

Unlike Luo, most presenters did not address the theoretical underpinnings of this shift away from state-society analysis head-on. Instead, turning to an analysis of space as an alternative to the conventional framework of state-society relations emerged as a popular approach. This interest in space spilled well beyond the single panel we had dedicated to the theme of spatial politics. As space often comes up as a term of analysis in both urban and global history, it was not surprising to see it take a prominent place at our conference. However, I would argue that in our case it represented not just an instantiation of current trends in related fields but also a response to the specific challenge that historians of China face in situating the state in historical narratives. On the one hand, scholars are aware that the field of Chinese urban history owes a great deal to the shift away from a state-centered analysis of cities: both because it spurred research on urban history “from below” and because it challenged the notion that the “Chinese” and “Western” city were fundamentally different. On the other hand, though, the state played an undeniably important role in many aspects of urban life and cannot be discounted.

Japanese Postcard of Victoria Park in the British Concession in Tianjin

Focusing on urban space allowed presenters at our workshop to negotiate this challenge because it encouraged us to consider how a variety of actors constructed, utilized, and managed space without necessarily attaching prima facie significance to whether they belonged to the state or not. (For further discussion of these historiographic stakes, see Chuck Wooldridge’s introduction to his 2015 book, City of Virtues: Nanjing in an Age of Utopian Visions.) Moreover, this was a constructive way to avoid a reductive understanding of “the Chinese city,” a problem which we had discussed in our opening panel because, again, discussions of space can readily accommodate histories of both transmission of spatial strategies from abroad and contestation within local contexts. Keeping these narratives at the forefront, even while we explored continuities across individual cases, reminded us of the complex nature of Chinese urbanities.

Stated in the broadest possible terms, the value of this workshop lay in demonstrating how a global perspective can enhance our understanding of the history of Chinese cities. More specifically, we saw how attending to global dynamics could help shed new light on long-running, nation-specific historiographic questions. There is value, then, both in learning from the research done by other scholars in global history and in hearing how their research addresses problems in respective national historiographies. By doing so we can integrate and mutually enrich national histories/historiographies and the field of global history.

Daniel Knorr is a Ph.D. candidate in Chinese history at the University of Chicago and a 2016-17 Fulbright Fellow. His research examines the relationship between state and place in Jinan, Shandong during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) through the lenses of cultural geography, elite networks, and public institutions.